|

The 1938 Pocket Book

|

||

|

No-Number #11

#11 #11

|

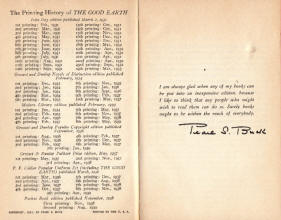

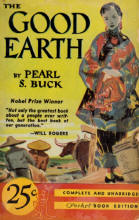

The book that started it all: the no-number Pocket Book released in November 1938, shown here next to a first issue of Pocket Book #11 (August 1939), which is a stated 2nd printing. I always assumed #11 was simply a reprint; when, in fact, it is a completely different book, sporting a different cover painting, 348 pages for #11, versus the original 378 pages, plus several other changes. One of the biggest oddities here is that I found a collector in Portland, Oregon, who had TWO copies of this book, and who was willing to sell me one. In more than 30 years of collecting paperbacks, I had never seen a copy for sale ... anywhere for any price. (Many thanks to collector/dealer Peter Fagnant, and to Ken Wector, who introduced me to him.) This is not the best copy in existence, but I am now able to share details with the vintage paperback community. Rarity has always been an issue with this book. It's mentioned in Jeff Canja's 2002 book, Collectable Paperback Books, in which he says that no price estimate can be assigned because he had seen no copy for sale in the previous decade. With a potential pool of a couple thousand copies out there, exactly how rare IS it? And why? After a fair bit of research, I've developed a hypothesis. While it is always mentioned in reference books, details are actually pretty sketchy. Most sources say that Robert de Graff ordered a print run of 2,000, and the test market was confined to the New York City area. There is no price on the book, and Richard A. Lupoff, in his book The Great American Paperback, says that de Graff circulated them (along with a questionnaire and an endorsement of the novel by Will Rogers) to prospective sales sites without charge. Piet Schreuers, in his book Paperbacks, U.S.A., notes that a cigar store near de Graff's office sold 110 copies and Macy's sold 695 on the first day. "Subsequent sales figures were equally encouraging, and the first 10 'official' titles soon followed." However, that was not the case. Those same numbers were used in Kenneth C. Davis' book Two-Bit Culture, when describing the first week's sales of the print runs of Pocket Books' first ten numbered books, distributed in June, 1939, also only in New York City. (In other words, it referenced sales for all ten books.) The stats are from Publishers Weekly, and it further notes that the Macy's sales figure came before they could even install a window display. After giving them the unnumbered test book, de Graff had gone back to Macy's hoping for a contract for 5,000 books, but they demanded 10,000 instead. Pocket Books would later claim that they had sold 107,000 books in the first three weeks of sales in June 1939. That would have almost matched the entirety of the first printings of those first ten books. SO, if we assume that the original 1938 no-numbered book was not intended for sale, and was simply provided to book and magazine outlets as samples, they would likely have been treated like ARCs (Advanced Reader Copies). Though the novel itself was not new, the format was a dramatic shift in the way American books were to be treated; and that concept was not well accepted by many people in the literary world. (Think of the way eReaders were thought of by book professionals twenty or thirty years ago.) In the past, ARCs routinely do not have the same longevity as first editions. In other words, many of de Graff's test books were likely discarded. In Graham Holroyd's Paperback Prices and Checklist (2003), he states that there were 2,300 copies of the 1938 book distributed, and that they contained a "tear out final page for a hardcover test-market distribution." My copy has no evidence of a "tear out" page; but he was probably talking about the blurb I've included here (immediately following the conclusion of the novel, and preceding the "About the Author" blurb). It's a weird little offer. It lists four hardcover editions of The Good Earth (for varying prices), and then says that if the reader tears out the last 30 pages of the paperback and returns them to the Pocket Books offices, it will give them 25¢ in credit toward the hardcover issue of their choice. I have no idea how many copies were destroyed in order to take them up on this deal. In conclusion, there is no way to determine how many copies of this book survive today. ARC's are routinely thrown away, and it is conceivable that some of the volumes were destroyed by sellers who objected to the dramatic shift in format. In addition, Pocket Books encouraged the destruction of the paperbacks using that little hardcover offer. As for the book itself: What's missing: Gertrude. You can read more about that in another "oddity." What's there: "Complete & Unabridged" on the cover. That was obviously intended to counter perceptions of the day that cheap, "mass market" publications often cut literary corners; a concept that was particularly driven by the popular conservative publication "Readers Digest," which often printed articles, stories and novels that were "Condensed for the Modern Reader." The declaration that the novel was unabridged would become a common one on the covers of the Pocket Books that followed. My copy lacks both the unattached endorsement letter and the questionnaire. If anyone out there has a copy of those that they'd like to share, I'd be happy to add them to this web page.

|

|

GoodEarth1938_small1.jpg)

GoodEarth1938_2_small1.jpg)

GoodEarth1938tp_small.jpg)

GoodEarth1938tv_small.jpg)

GoodEarth1938endpapers_small.jpg)

1938post1_small.jpg)

1938post2_small.jpg)

GoodEarth1938back_small.jpg)